Answers to Questions re Service Academy Admissions and a Change to the Mission Statement

28 March 2024 2024-03-28 15:09Answers to Questions re Service Academy Admissions and a Change to the Mission Statement

Answers to Questions re Service Academy Admissions and a Change to the Mission Statement

By Scott McQuarrie, USMA ’72

President, Veterans for Fairness and Merit

A USNA grad emailed some perceptive questions about service academy admissions. They touch on the changed USMA mission statement only slightly.

My answers explain some of the admissions processes and some of the evidence (recently revealed in court filings) that would surprise most graduates.

Some of you might be interested, so I am pasting my reply, below. Because the questions were detailed, the answers get a bit deep in the weeds. If you have no interest in what is actually occurring in academy admissions, read no further. Feel free to forward.

At each academy, the full number of possible congressional vacancies (5 per Member at any one time) is never used. That is because some Members don’t use their authorized vacancies, and some who do don’t have enough applicants who are qualified to have 5 at an academy at any one time.

On the other hand, there are some Members who represent districts that have high concentrations of interested and qualified applicants for one or more of the academies (the DC metro area is a good example) so they always have 5.

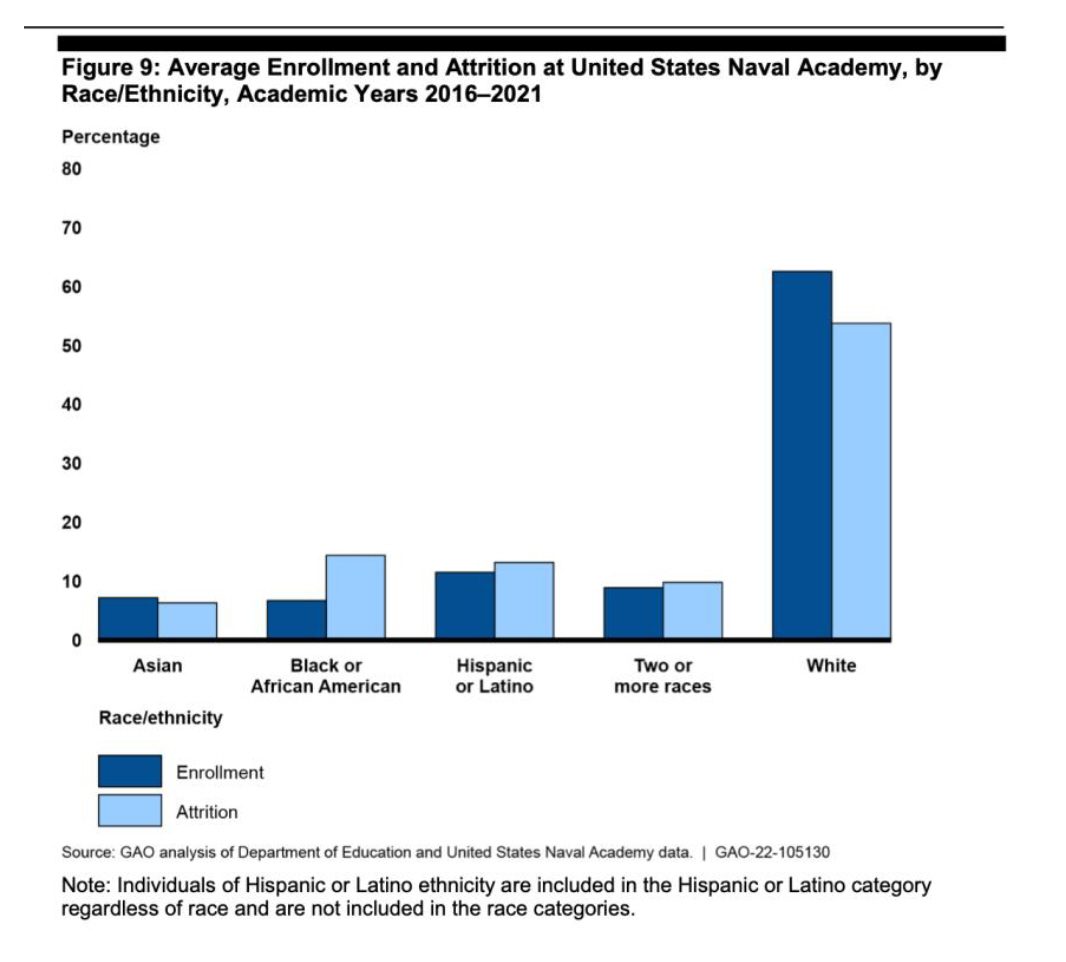

USMA and USNA admissions are governed by almost identical statutes and, I believe, their practices are very similar so that their entering classes are similar in most of their demographics.

At USMA, the entering class of 2026 (n=1219) had 521 congressional “vacancy winners” and 150 “Qualified Alternates” (almost all of whom were congressional nominees who did not win their congressman’s vacancy, but who were in the “top 150” (highest 150 candidate composite scores, at USMA called “Whole Candidate Score,” at USNA called “Whole Person Multiple”) on the National Waiting List and thus had to be offered an appointment in the “Qualified Alternate” (“QA”) appointment category.

That 150 QA number is actually measured by how many accept QA appointments, not the number that are offered – they don’t stop offering at 150 because some QA offerees decline the appointment, and the academies must fill 150 QA slots that way per the statute.

Thanks to Rep. Mike Waltz (R – FL), starting with the class of 2029 (the admission cycle for which will begin later this spring and end in June 2025) the 150 number for QAs will change to 200. QA appointees do not count against the 5 congressional vacancy limit per Member of Congress.

Some Members have many more than 5 constituents at an academy at any one time. Only the “vacancy winners” count against a Member’s statutory allotment.

You asked how the other vacancies are filled (521 congressional plus 150 QAs does not come close to 1219).

There are various other appointment categories:

- Presidential – max 100

- Superintendent – max 50

- ROTC/JROTC – max 20; enlisted reserve

- SecARM – in practice, Prep School) – max 85

- enlisted regular (SecArm – mostly Prep School) – max 85

- children of KIA/disabled (65 vacancies at any one time, so avg ~ 16 max annually)

Not all of those vacancies are fully used, either. So that leaves vacancies that are filled using a separate appointing authority called “Additional Appointments” or “AAs.”

At USNA in the class of 2026 there were 310 AAs, and class of 2027 255 AAs, so average 283.

At USMA in classes of 2021-2027 there were an average of 282 annually. That average number works out to about 23% of the entering class, which, importantly, is the second largest appointment category in the class (behind only congressional (43% for USMA Class of 2026)).

Unlike QAs, Additional Appointees do not have to be selected “in order of merit.”

So, USMA allocates their AA appointments to applicants who were not selected (because they were not competitive) in any other category and who are in certain demographic categories, “class composition goals” which USMA is trying to meet.

For the USMA class of 2027, the AA appointments went to

- Recruited Athletes – 183

- African Americans – 76

- Women – 74

- Hispanics – 54

(total of 387 exceeds actual AA total (for that year, 364) because those demographic categories can overlap – if for example a Recruited Athlete is a Hispanic woman, that appointment would count in each class composition goal category for AA numbers).

It would be rare to find a White or Asian male who is not a Recruited Athlete among the Additional Appointees.

Relatedly, we know from USMA documents recently revealed in litigation that different candidate composite score minimums are used depending on the applicant’s demographic category.

For the academies’ equivalent of early acceptance (called Letters of Assurance, or LOAs, receipt of which is helpful/if not essential when competing for a nomination), at USMA the Whole Candidate Score minimums to qualify are stated as follows:

- Recruited Athlete (none stated)

- African American (none stated), Hispanics – 5600

- Scholars (any race or gender) – 6800

- Women – 6500

Effectively, if an applicant is a white or Asian male and not a recruited athlete, his composite score must be 6800 or higher to qualify for an LOA. These thresholds are adjusted during the admissions cycle, but the pattern is established early and is clear.

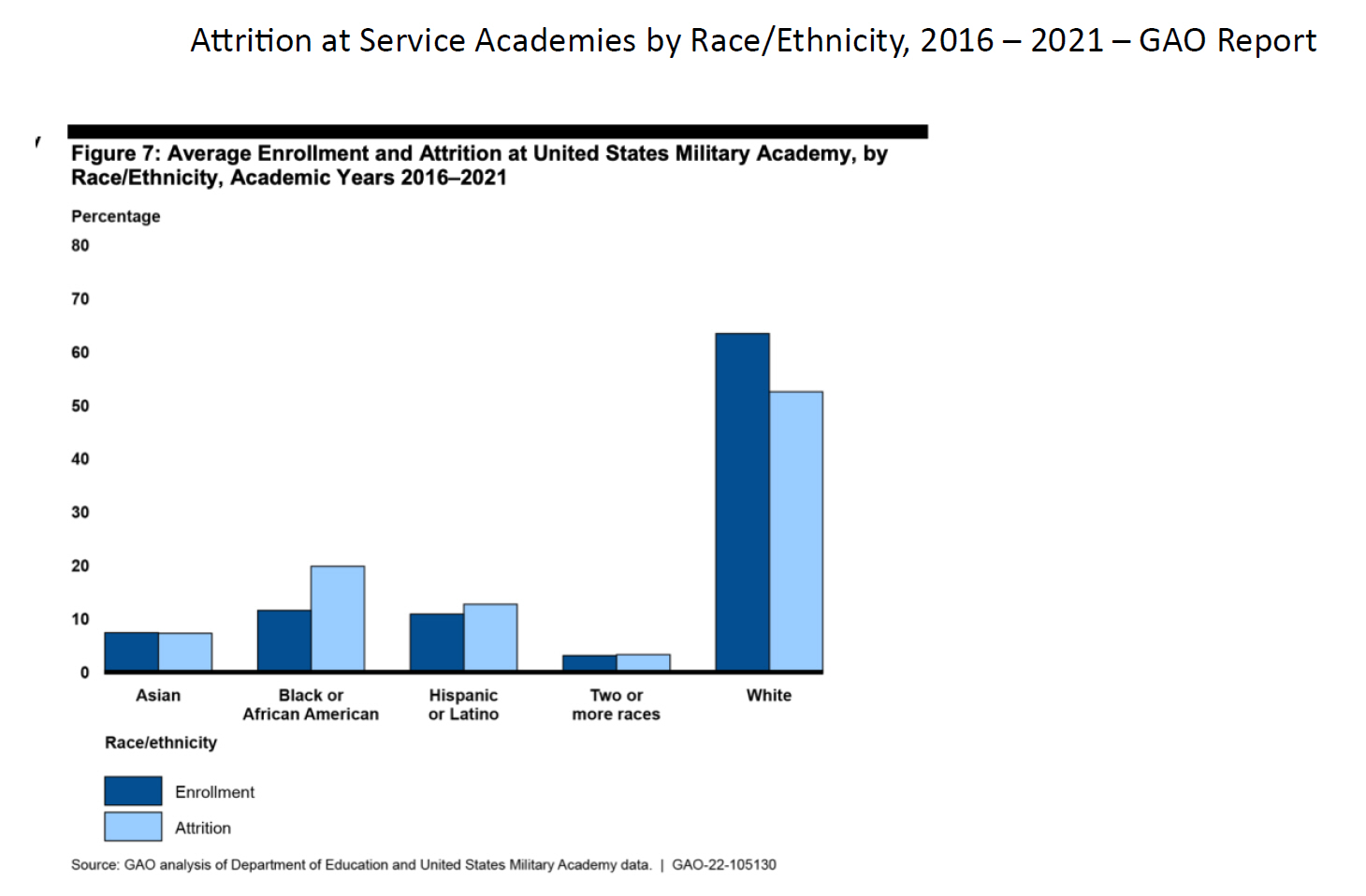

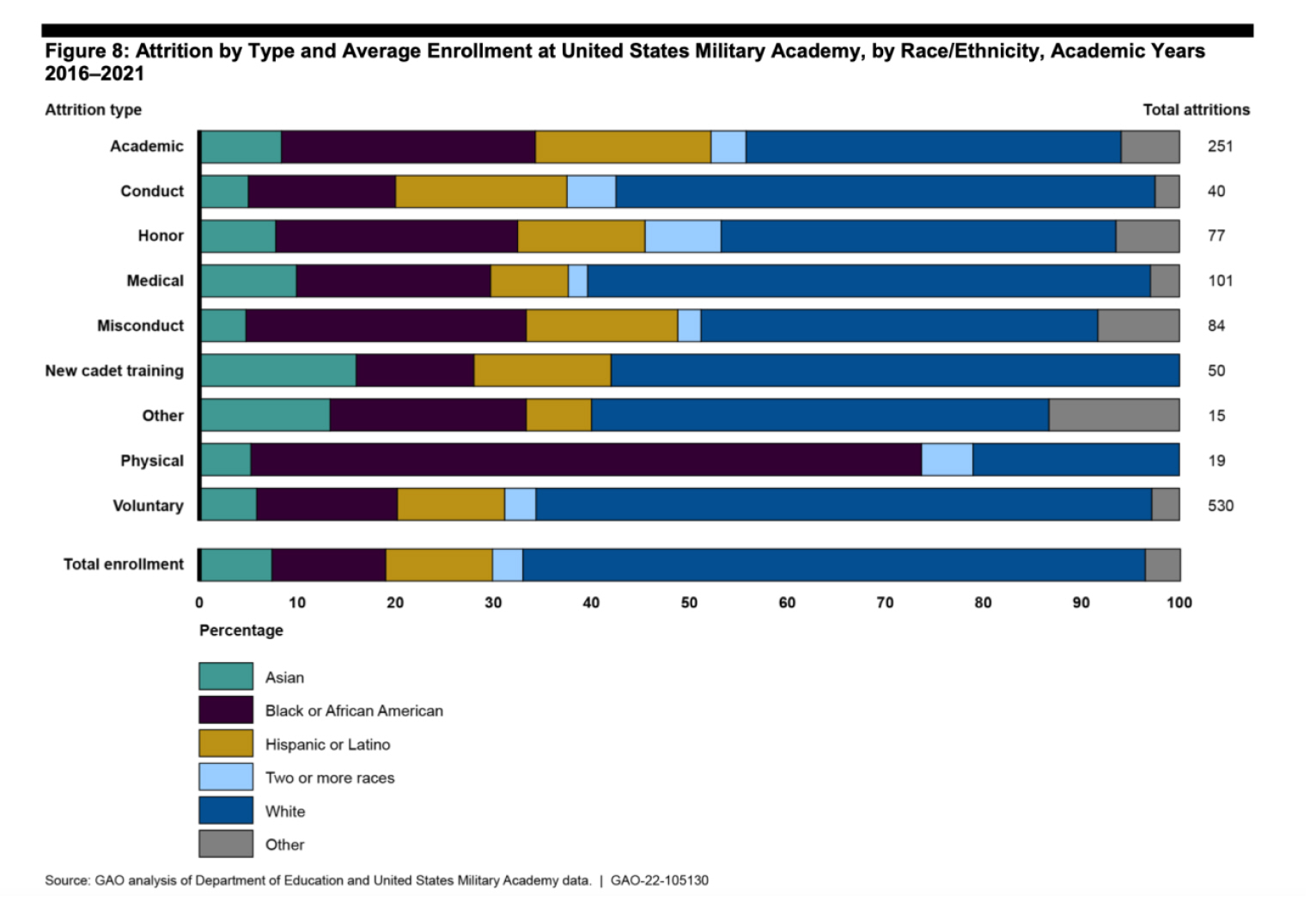

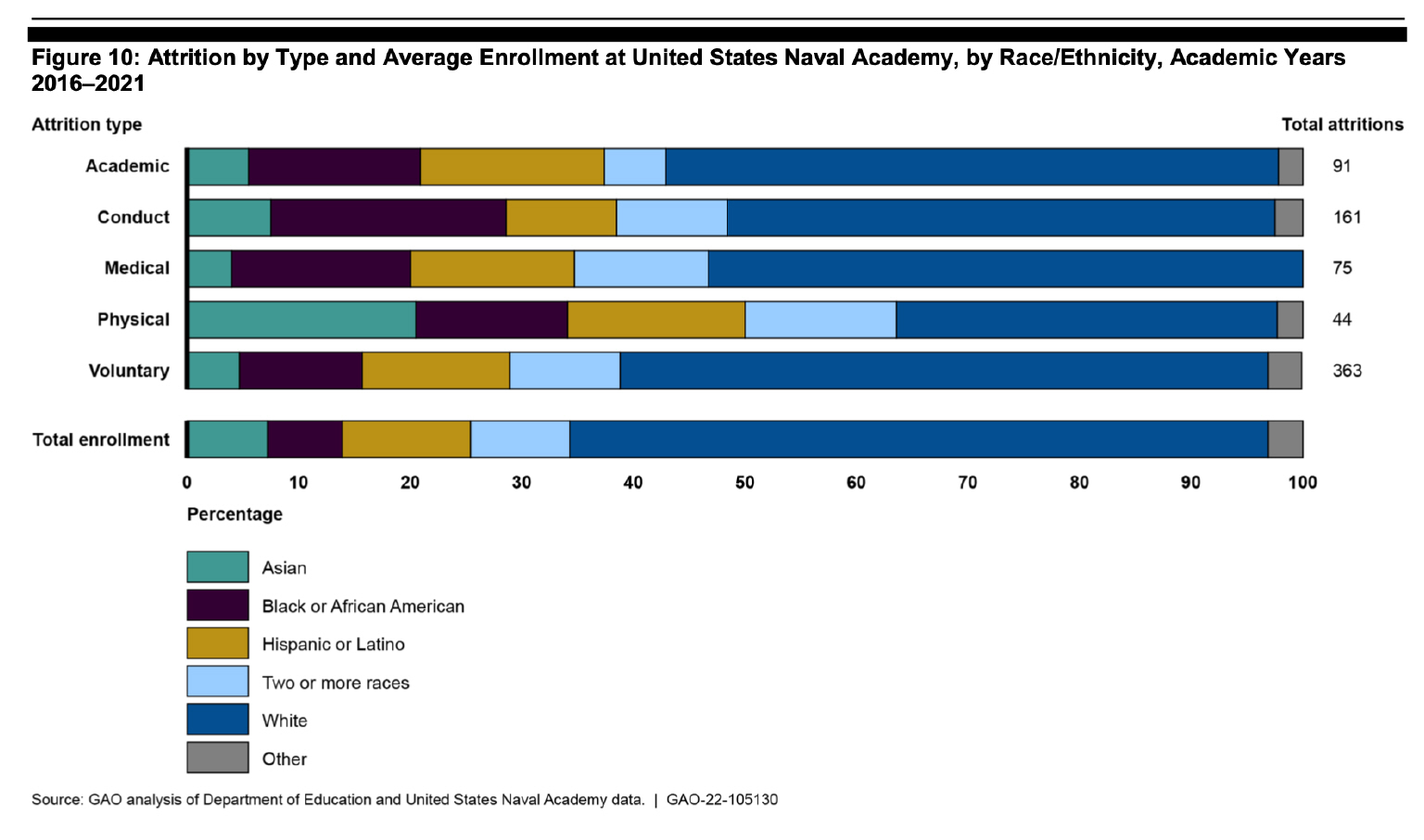

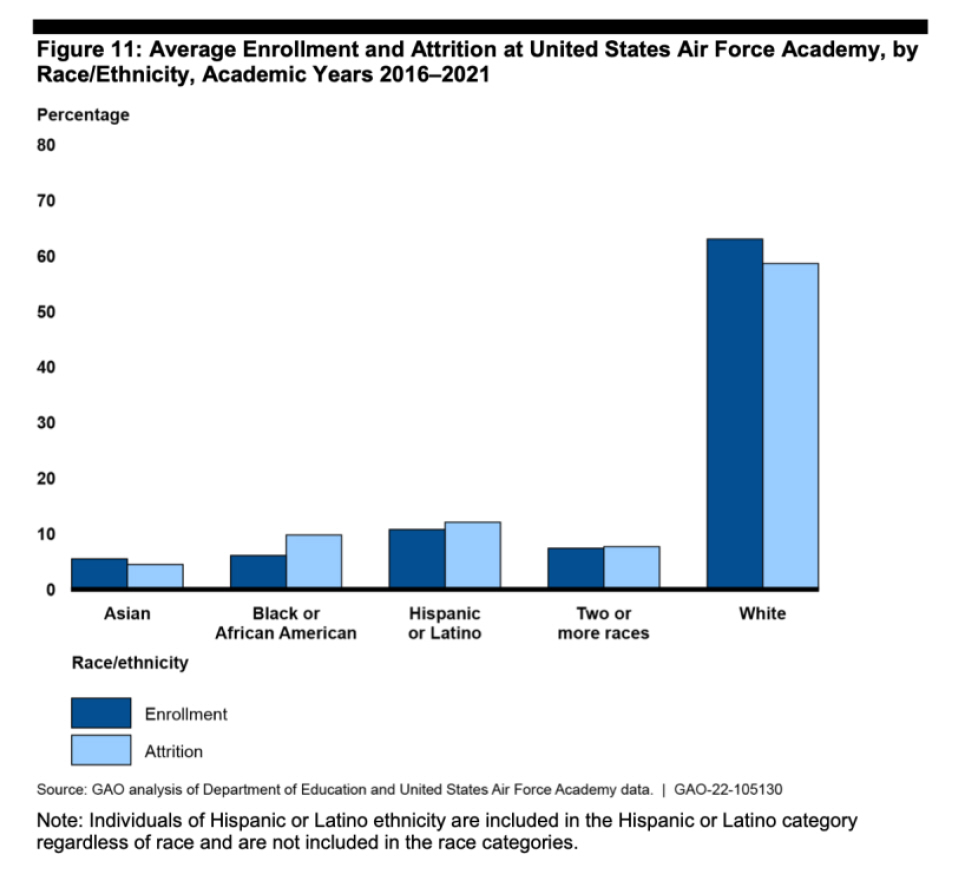

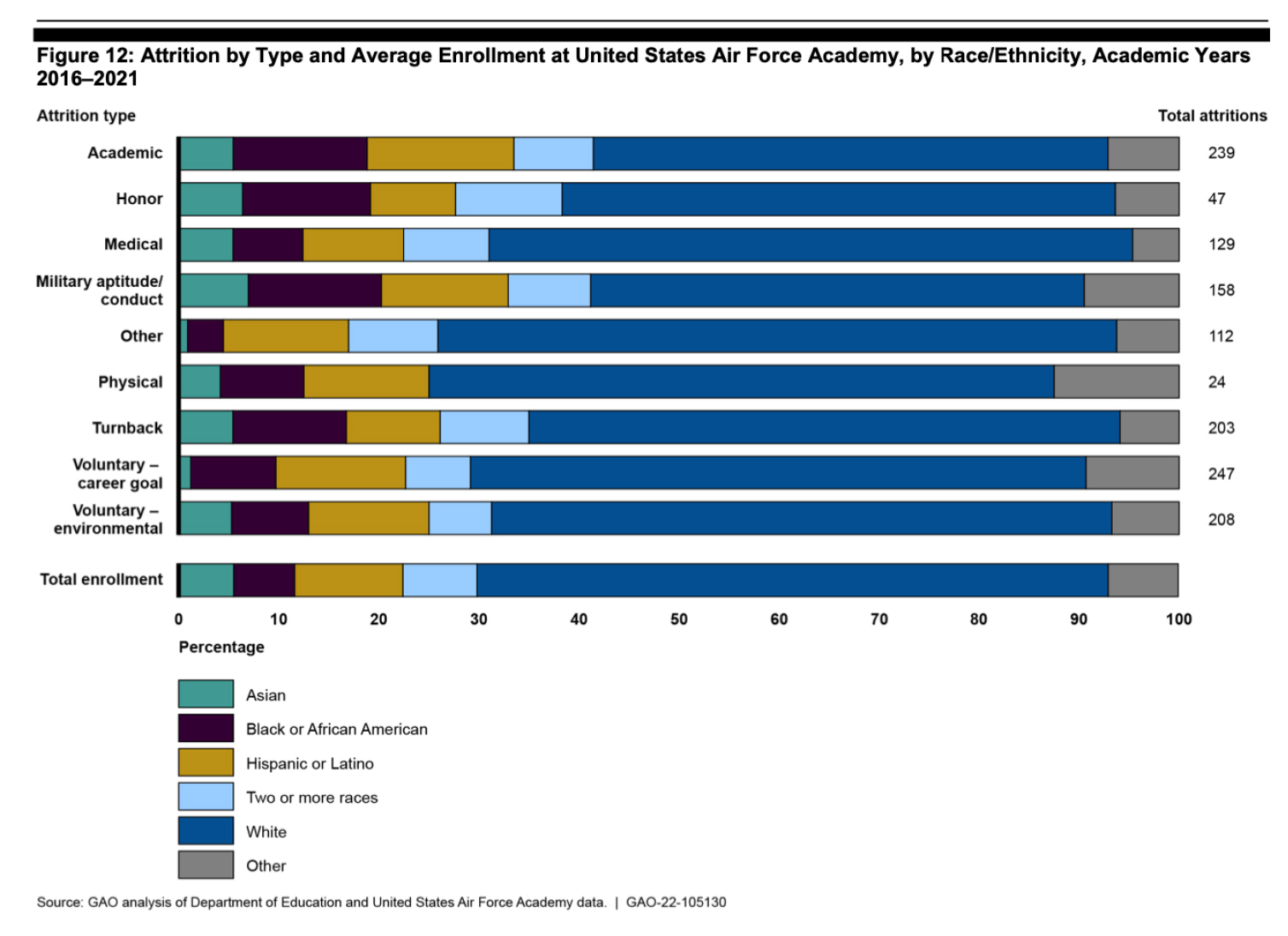

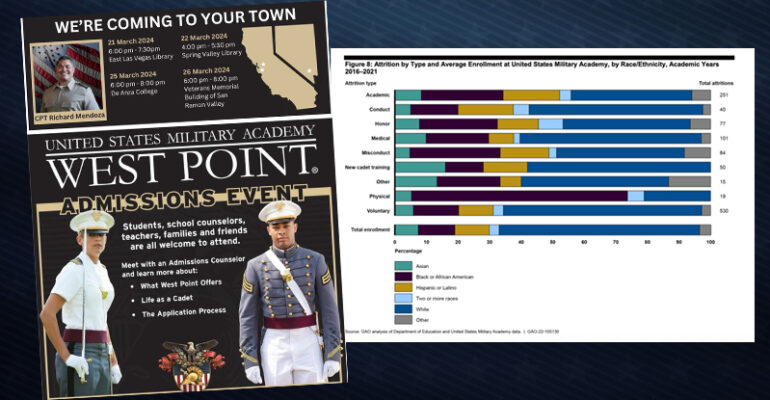

I don’t have perfect data to answer your question re performance of marginally qualified appointees, but look closely at the below 2022 GAO data by demographic category for attrition rates and reasons for leaving at each of the academies, noting the disproportionality by demographics in some reasons for leaving.

A corollary question should be, what are the qualifications (candidate composite scores) of the candidates who are deemed qualified for admission but who don’t get selected as Additional Appointees (and thus are not admitted) compared to the qualifications of the Additional Appointees?

Are the rejected candidates’ composite scores (remember, composite scores are the academies’ own, finely tuned, metric for determining who is the best qualified candidate) lower or higher?

If higher, how much higher?

What is the race of any non-selected candidates who have higher composite scores compared to those of the Additional Appointees?

USMA claimed in a filing at SCOTUS in January 2024 that the impact of considering race in admissions decisions is “almost imperceptible.” The GAO data and a 2015 RAND study results strongly suggest otherwise.

The truth has been successfully concealed from Congress for decades.

But (with litigation ongoing) when one reads that one of USMA’s 2024 strategic Lines of Effort is to “Build and Retain Diverse and Talented Winning Teams” and the mission statement inexplicably adds the word “Build,” given the above knowledge, what has been occurring behind closed doors begins to come into focus.

The academies know what they have done and, to the extent it will be discovered by SFFA’s attorneys, what they may have to defend in court.

Their defense in ongoing litigation is that considering race in admissions decisions is a “national security/strategic imperative.”

Having USMA’s 2024 Strategic Lines of Effort include building and retaining diverse and winning teams, and adding the word “build” to the mission statement, are perfectly consistent with their primary (“strategic imperative”) defense.

Only someone who is naïve would believe that USMA’s or DoD’s attorneys had no input to this new mission statement.

Click to enlarge